This is a guest post from Lars Erik Schönander, a policy technologist at the Lincoln Network.

After a decades-long hiatus, industrial policy is back in vogue. The Biden administration will invoke a law passed in 1950, the Defense Production Act, originally designed to build America after World War II, to raise production of everything from solar panels to baby formula.

Industrial policy could address the shortages that are hurting the US economy. But the United States is still all over the place. The US should look to Japan to learn the art of strategy.

From the 1950s to 1980s, Japan was the world’s model for a successful industrial policy. The Japanese government organ MITI, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, was the body that planned and executed industrial policy. Here are the three biggest lessons learned:

ASIMO, the advanced humanoid robot created by Honda. Used with permission from Getty.

Coordinate the silos and bring together civil servants

While the US has no single agency tasked with industrial policy, MITI was the one industrial agency in Japan. It offered state financing to firms through the Japanese Development Bank and deployed the Japan External Trade Organization to collect commercial intelligence. MITI was a full-stack operation, charged with bringing success to Japanese companies in the competitive global economy.

America’s industrial policy is scattered and siloed between the White House, Congress and federal agencies, leaving civil servants disempowered and unable to make clear decisions. Congress writes industry-friendly bills, and the White House invokes the Defense Production Act (as President Biden did) to fund the manufacture of strategic goods. Meanwhile, the Department of Energy calls upon its own body, the Advanced Research Projects Agency. The National Institute of Health deploys its seed fund.

Like in Japan, agencies need to communicate about their industrial policy plans. We have some precedents. In 2020, the Department of Defense reached across the silo and dispensed funding to Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), a project funded by the Small Business Administration. The companies received Defense Production Act Title III funding. We need more coordination like this.

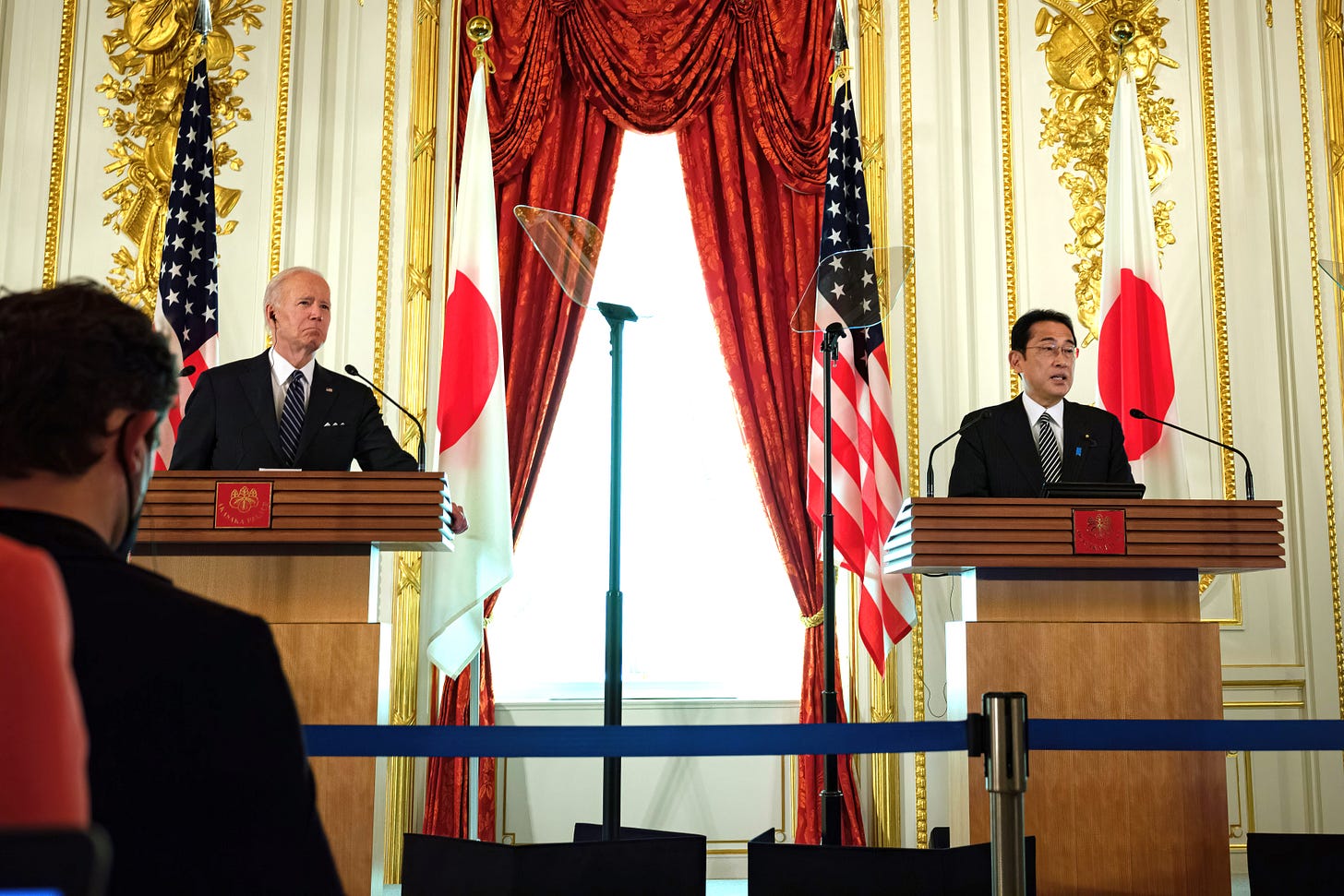

President Biden visits Tokyo on May 23, 2022. Used with permission from Getty.

2. Companies and the government need healthier relationships

The Japanese government is well-known for having close relationships with corporations. But Japan is not the only country to embrace the model. The United States has its military-industrial complex in which Raytheon or Lockheed work with the federal government. What’s unusual about Japan is that non-defense companies, working outside the military-industrial complex, also benefit from close ties with the state.

The United States doesn’t need to go as far as Japan in creating closed-off networks between bureaucrats and businesspeople. But we can still adopt some good practices. We could, for instance, set up an agency in the Department of Energy that manages funding for private climate-related businesses, instead of relying on one-off announcements from President Biden, like when he announced $3.5 billion for carbon-capture projects on May 19.

America can establish an agency of industry and innovation in, say, the Department of Treasury, to help wrangle all these one-off initiatives into a coherent industrial strategy.

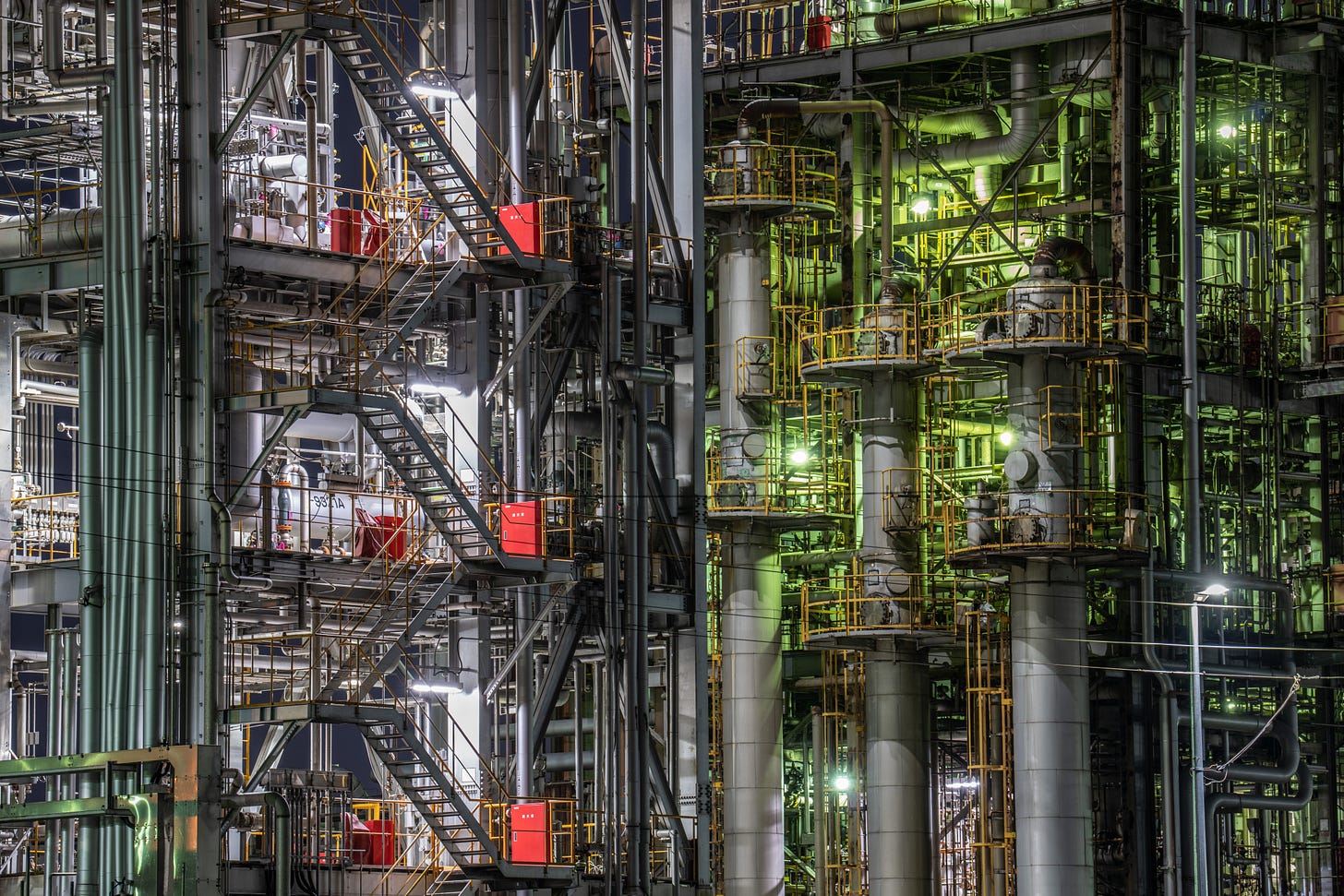

A chemical plant in Kawasaki, Japan. Used with permission from Getty.

3. Think about long-term planning

Japan’s MITI as an institution was capable of working towards long-term goals, anticipating major market movements rather than reacting to them.

MITI’s strategy was to provide funding, support and market protection through tariffs to the firms of a promising but infant industry, such as the early semiconductors in the 1950s and 1960s. Over time, as those firms grew and became profitable, MITI weaned them off state support but held onto limited regulations that helped them globally.

US industrial policy is fundamentally reactive to the market, doling out funding and support after a crisis. An example of this can be seen with our energy industry. While oil and gas companies are making record profits, they are not investing in expanding their production capacity. As the Dallas Fed reported, despite energy companies making record profits, they are returning their profits to shareholders.

Hi, Geof! This post was spot on up to the last paragraph, where the author regretted that oil and gas companies are not investing their record profits in expanding their production capacity. The world does not need more oil and gas production capacity. Like BP, Shell and Total, US oil giants Exxon, Chevron et al. should refocus on bringing non-carbon technologies to market.